As flu season picks up and experts weigh concerns about another possible COVID surge, children’s hospitals are already filling with patients with another viral threat: respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. Even though many people haven’t heard of RSV, pretty much everyone has had it, probably multiple times, says Anthony Flores, chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and a physician at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital. RSV is the leading cause of bronchiolitis—inflammation of the lung’s small airways—in infants, and the virus is so common that nearly all children have encountered it by their second birthday.

|

| Credit: Nfid.org |

“It’s that ubiquitous,” Flores says. “Even adults are exposed to it repeatedly over time, so we develop some immunity to it.” In healthy adults and children, though, RSV typically presents as a common cold, with symptoms similar to those caused by other “common cold” viruses, such as rhinovirus, adenovirus and a couple of common coronaviruses. But that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. RSV costs the U.S. more than $1 billion each year in health care costs and lost productivity, and it can be particularly dangerous for newborn babies and adults older than age 65.

“As we have come to learn, particularly gradually over the last 15 years, this is a virus that annually produces probably about as much illness in adults as does influenza,” says William Schaffner, a professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. That’s because our immune system ages along with us. “As we get older, our immune system doesn’t work as well,” Flores says.

The good news is that RSV vaccines are on the way. In fact, Pfizer just announced this week that its maternal RSV vaccine—given during pregnancy so that antibodies are transferred through the placenta to the fetus—was 82 percent effective at preventing severe RSV in babies through three months old. But until the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves a vaccine, RSV will be one of the unavoidable viruses people encounter each year.

What is RSV, and what are its symptoms?

RSV is an RNA virus made up of 11 proteins, similar to influenza A, another RNA virus whose genes encode the same number of proteins. It infects the nose, throat, lungs and the breathing passages of the upper and lower respiratory system, according to the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. As the body sends immune cells to virus-infected cells to fight the disease, it causes inflammation in the airways.

Symptoms include a runny nose, reduced appetite, coughing, sneezing, wheezing and sometimes a mild fever—although fever is more common in young infants and older adults. Symptoms show up about four to six days after infection and take one to two weeks to resolve.

How is RSV transmitted?

RSV spreads primarily through respiratory droplets from coughing, sneezing and kissing (transmission by airborne droplets, or aerosols, has not yet been shown). But the virus can also survive for several hours on hard surfaces, including tables and crib rails. Such “fomites” are a more common mode of transmission for RSV than they are for COVID. People infected with RSV are typically contagious for about three to eight days, even if they don’t have many symptoms.

The basic reproduction number, or R0, for RSV is estimated to be around 3, which means a single infection of RSV will lead, on average, to three other infections.

How severe is an RSV infection?

For the average person, RSV is little more than a nuisance, Flores says. “For most of us—children over the age of two and healthy adults—it’s just like a common cold,” Flores says. “It may give us a little bit of a cough and runny nose, maybe a mild fever, but we usually get over it pretty quickly.”

But infants under six months old, and especially those under two months old, have a harder time with RSV. “That’s where we see our highest hospitalization rates [in children]—maybe three or four times higher in that age group than in others,” Flores says. The reason is basic physics. “It has everything to do with the size of their airways,” he says. Their airways simply aren’t wide enough yet to allow airflow with all the inflammation caused by the immune system’s response to the virus.

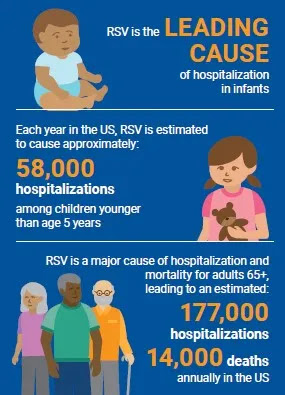

Even then, only about 1 to 2 percent of children under six months with RSV need hospitalization (usually for a couple of days), and death is rare. An estimated 58,000 U.S. children are hospitalized with RSV each year, and the virus kills about 100 to 500 U.S. children under five each year. (Since the pandemic began, COVID has killed more than 560 children under five, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) Premature babies and those with underlying heart and lung conditions have the greatest likelihood of complications and hospitalization. Premature infants’ lungs tend to be underdeveloped and even less capable of handling the inflammation caused by the virus. In fact, children who meet strict criteria for being at highest risk are recommended to receive the preventive antibody medication palivizumab as an injection into the thigh muscle once a month when RSV is circulating.

Adults older than age 65 are also at risk of severe RSV, although public health officials have only begun to recognize the threat to older adults in the past decade. Every year an estimated 177,000 older adults are hospitalized with RSV, and about 14,000 die from it. For comparison, influenza kills anywhere from 21,000 to more than 44,000 adults older than 65 each year.

Another population at higher risk for complications from RSV are people who are immunocompromised, whether because they have an underlying condition that weakens their immune system or because they take a medication that suppresses it. Those who have had organ transplants, for example, take medications that dampen their body’s immune response to avoid rejection of the new organ. And many of the drugs used to treat autoimmune conditions also weaken the immune system.

Why are cases surging now?

Historically, RSV season was so reliable that children’s hospitals planned staffing around it. It typically ran from about November through April, with the biggest peaks in January and February, depending on local conditions. But the pandemic changed everything. With many people staying home, social distancing, washing hands and wearing masks for most of 2020 and into 2021, RSV—like influenza—never really arrived, and its seasonality has been out of whack ever since.

“All of a sudden, last summer, we had this huge surge of RSV,” Flores says. “At it first baffled everybody, but then it kind of epidemiologically made sense.” Normally, most kids encounter RSV some time in their first year and a half of life and develop some immunity as they recover. The immunity doesn’t last very long, but enough of it lingers that subsequent infections aren’t as severe. But thanks to the social distancing and masking, a whole birth cohort of kids had never been exposed to RSV before. So as society began opening back up in the summer of 2021, all of them were exposed at once, and RSV roared back like it was Christmas in July.

“We tended to see more severe reactions, so we saw more hospitalizations, and I think it’s because we had a larger pool of kids who had never been exposed to RSV in the past,” Flores says. That summer surge eventually settled down, but fast-forward to 2022, and although it’s later in the year, something similar is happening.

On one hand, current pediatric hospitalizations aren’t much higher at Flores’s hospital and many other hospitals than they would be during a typical RSV peak in midwinter. But the problem is that it’s not midwinter yet. With flu cases rising, pediatricians and public health experts are asking themselves the same question: “Are we going to see another surge with COVID later this year and then see a ‘tripledemic’?” Flores says. “That’s the big worry.” Flores doesn’t think a triple surge would necessarily cause more deaths, but it would place a significant burden on the health care system that many places aren’t prepared to weather.

Is there a vaccine for RSV?

There is no approved RSV vaccine yet, but there likely will be soon. Scientists have been working on such a vaccine for half a century, but a disastrous trial in the 1960s resulted in the deaths of two toddlers who caught RSV after receiving the vaccine. It turned out the disease was more severe in those who were vaccinated, and until that mystery was resolved, not much progress occurred. Fortunately, one of the same scientists whose team determined the spike-protein mRNA code for the COVID vaccines, Jason McLellan of the University of Texas, solved the RSV vaccine problem with virologist Barney Graham, then at the National Institutes of Health, about decade ago. Now that work is coming to fruition.

Several pharmaceutical companies began vaccine trials with McLellan’s protein in 2017, and the first successful phase III (late-stage) results came this year. Pfizer’s vaccine was 86 percent effective, and GSK’s was 83 percent effective in adults 60 and older. Between those vaccines and Pfizer’s recent maternal RSV vaccine news, Graham, who is now retired from the NIH, expects to see at least one RSV vaccine approved by the end of 2023, if not sooner.

How is RSV treated?

There is no medication to treat RSV, so the treatment is primarily supportive care for symptoms such as fever and congestion. Those who have trouble breathing may receive a breathing tube or supplemental oxygen through a mask or nose tube. The American Academy of Pediatrics used to recommend steroids for infants, but the data are conflicting on how well they help, so that’s no longer a standard recommendation, Flores says.

There are a couple of reasons therapeutics don’t exist for RSV. First, it’s very difficult to develop effective drugs for respiratory virus infections. Most of the four antivirals available for flu, for example, are fairly new and have limited effectiveness unless given early after infection. Second, so few children die from RSV that therapeutics weren’t as high a priority as developing drugs for other conditions. The recent understanding of how many adults die from RSV and advances in monoclonal antibodies, however, have boosted the pipeline for new RSV treatments.

The drug furthest along is nirsevimab, which was 75 percent effective in healthy infants in a phase III trial and has been shown to be safe in premature infants as well. FDA approval could come late this year or next.

What should someone do if they think they or a family member has RSV?

Chances are, you won’t know if you have RSV because it will feel like any other cold. You should do “all those things we’ve learned in the pandemic” when you’re sick, Flores says. That means wearing a mask, practicing good hand hygiene, covering your mouth when you sneeze or cough and, for those able to do so, working from home. Many people won’t or can’t stay home from school or work with just a cold, though, so wearing a mask can at least protect others around you while you’re sick, especially those at higher risk for complications. If there’s anything we learned from the way flu and RSV basically disappeared in 2020, Flores says, it’s that masking obviously works.

When should someone with RSV go to the hospital?

As with any other respiratory illness, the biggest sign that one should seek medical attention, regardless of age, is having difficulty breathing, Flores says. In addition, parents should take an infant under six months to the doctor or hospital if the child can’t lie down without breathing difficulty, if they’re sleepier than usual or if they’re difficult to rouse from sleep.

What can one do to protect vulnerable people from RSV?

Infants and young children who were born premature or who have weakened immune systems, chronic lung disease, congenital heart disease or a neuromuscular disorder may qualify to receive the drug palivizumab. Palivizumab is very expensive and in limited supply, so it’s reserved for those at highest risk, who will receive the most benefit from it. When the RSV season was more predictable, at-risk infants would begin receiving palivizumab in late fall, but when RSV’s seasonality shifted in 2021, state public health authorities convened to ensure the drug would become available when cases began rising.

For others at risk, including infants without underlying conditions, older adults and immunocompromised individuals, the same protections they take against COVID are also effective against RSV, as the low rates of RSV in 2020 showed. “When we see these surges like this, [vulnerable people are] absolutely instructed to be more careful,” Flores says. That means not having sick family members visit, washing hands regularly and wearing a mask outside the home to prevent not only COVID but also exposure to all the other seasonal respiratory viruses, including flu and RSV. And of course, Flores says, everyone eligible for a flu vaccine and COVID vaccine should ensure they’re vaccinated and boosted to reduce the risk of developing multiple infections at the same time.

CDC issued a Health Alert Network Advisory about increased respiratory virus activity, especially among children. Co-circulation of respiratory syncytial virus RSV, influenza viruses, SARS-CoV-2 & others could strain healthcare systems this fall & winter. https://t.co/02GSogRvWd

— CDC (@CDCgov) November 4, 2022

Comments

Post a Comment